Magical, Mystical Darjeeling: Taking Tea in the Clouds (Part I)

This article is from the Tea & Coffee Trade Journal (July '04). This publication contains many interesting articles on both tea and coffee. It is a great place to learn about tea and the growing regions.

|

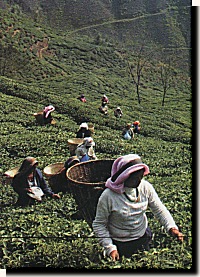

As the clean, clear mist crosses the silent, vast Himalayan range there is heard a gentle rustling. It is the beautiful, colorfully-dressed women moving slowly through invisible paths across the rolling hills of the Darjeeling tea gardens, skillfully plucking the finest of the delicate leaves from the bushes and dropping them into the soft, green piles forming inside their baskets. Majestic, snow-capped mountains surround them, forming a stunning backdrop. It is a scene as rare and special as the beverage that is the product of their work. Darjeeling is a remote corner of the world where golden-colored monkeys romp by bridges near waterfalls, where tall fir trees stand silently in the valleys as they have for centuries, where long, winding stairs lead up to brightly-colored temples built so high they seem to reach the clouds. The air is filled with the delightful songs of birds of every hue. There is no doubt that the quality of the tea produced here is affected by the magic of its fairy tale surroundings.

Darjeeling tea is born in the foothills of the Himalayas, in the shadow of the third highest mountain in the world, Mt. Kanchenjunga. The Darjeeling district is located in West Bengal in northeastern India, with Tibet, Nepal and Bhutan to the north. The area, whose altitudes range from 6,000 to over 8,000 feet, was mostly unpopulated forest until the British won it from Nepal in 1816 and turned it into a hill station for its military. Soldiers travelled to its health sanitariums, where the cool mountain air and serene setting helped them recuperate from illness and fatigue. In 1835 the region was ceded to the East India Company. Dr. A. Campbell, Darjeeling’s first Superintendent, experimented with planting tea seeds in the area, and in 1847, the government began growing tea commercially. Darjeeling was still only sparsely populated, so labor for the plantations was recruited from Nepal. By 1874, there were 113 tea gardens in Darjeeling grown over approximately 6,000 hectares. By the end of the 1970s, most of the gardens were bought from the British by Indians, who were usually already managing the estates themselves.

|

A Tea Like No Other

The first tea seeds planted were of Chinese origin brought in from the Kumaon hills of north India. To this day the China variety of tea is planted in Darjeeling, and it has been discovered that, when planted anywhere else in the world, the Darjeeling taste cannot be reproduced. It is just something about the hills of Darjeeling that makes tea. . . Darjeeling. Tea gardens are situated at up to 7,000-ft-high elevations on steep slopes, which provide ideal drainage for the generous rainfall the district receives. The altitude, the soil, the intermittent cloud and sunshine - and a dash of something unexplained and wondrous - all seem to work together to orchestrate a masterpiece.

Often referred to as the “champagne of teas,” a cup of Darjeeling tea is golden or amber in color and has a unique, delicate flavor that is referred to as “muscatel,” or, having the flavor of muscatel grapes. The typical flavor can also be described as “flowery,” and sometimes, “peachy.” So delicate and tasty is the flavor that drinkers usually skip the milk and sugar often added to the more bitter, heavier black teas. Darjeeling connoisseurs literally cringe at the thought of adulteration.

Today, Darjeeling produces almost 10 million kilos of tea a year - only 1% of all of India’s teas. There are 86 gardens producing Darjeeling tea on a total area of 19,000 hectares, spread over seven main valleys. The gardens are called by English, Indian or Nepalese names, many of whose origins tell parts of the story of Darjeeling. Marybong, Ging, Tumsong, and Chamong, Lingia, Sungma, Nagri. . . each is situated in its own special place in the mountains that grants each garden’s tea its own distinctive flavor. Its functions are painstakingly run and watched over both day and night by the garden manager, each of whom lives among their tea fields in century-old British-style bungalows along with their families. Their neighbors are their employees, who live on the estates as well, forming what are, essentially, small villages.

Like a fine wine, Darjeeling also commands the highest prices for tea in the world. Aside from its unique taste, there are several reasons for this. First of all, there is less of it than other teas. “Darjeeling has an annual yield of 500 or 600 kilos of tea a year of finished product. In the plains, the yield is about 2,000 kilos a year,” says Sanjeev Seth, secretary and spokesperson for the Darjeeling Planters’ Association. In fact, the quantity of tea that is produced among the mountains of Darjeeling in one month can be produced in just one day in the plains, like those of nearby Assam. The hilly terrain here is more difficult for pluckers to navigate, making the plucking a slower process, and Darjeeling leaves weigh less than other varieties, due to a more severe withering process and smaller leaves.

|

The processing Darjeeling goes through is the very exacting, time-consuming “Traditional” or “Orthodox” method, which costs about five times as much to execute than the “Unorthodox” method used to process other teas.

Every prized gem has its counterfeiters, and a good deal of tea over the years from other areas has been sold under the Darjeeling name. In 1983, the Darjeeling Planters’ Association launched a Darjeeling logo, but found that even still, four times the amount of Darjeeling produced was being sold. Four years ago it was made into an official certification trademark, which can only be used if the tea is 100% Darjeeling, and there are specific boundaries set on what qualifies as Darjeeling. So today when you see the Darjeeling logo, it guarantees that 100% of that tea was grown and processed in the area that yields the true Darjeeling taste.

Growing in the Land of the Thunderbolt

The name “Darjeeling” comes from the Tibetan words dorje and ling. Dorje literally means “indestructible hardness” or “thunderbolt of enlightenment” and ling means “place.” Darjeeling is referred to interchangeably as “Land of the Thunderbolt” or “Land of God.” Both seem to be true. Beyond the stunning natural beauty of the Himalayas, and its diverse array of animals, birds and plant life, Eastern religions thrive here. Buddhism and Hinduism are widely practiced. Buddhist monastaries abound, many founded by Tibetans who fled to India along with the Dalai Lama after their people were massacred by the Chinese in 1959. One need only to pass a barber shop to see the monks in their robes having their heads shaved, or look at the “third eye” marks on most residents’ foreheads, to get a glimpse of the spiritual nature of Darjeeling’s inhabitants.

“Land of the Thunderbolt” also has a literal meaning. Tea, an evergreen tropical plant, needs a lot of rain in order to grow, and storms pay an integral role in the cyclical growing of Darjeeling. Rajah Bannerjee, owner of Makaibari Tea Estate lyrically explains that the banghi period is when the area is hit by “norwesters,” with “fast-moving clouds and thunderstorms,” just after the First Flush, which is from March to April. “After this bounty, a slack, and they sleep.” He goes on: “There are intense summer storms,” he says. “Then… overnight, a riot of green - activity, cats, birds myriad lifeforms. The second flush emerges with it.” The Second Flush here is from April to June. Then there are the monsoons, when it “rains for 21 days.” In mid-September the monsoons end and the Autumnals are grown until November.

Darjeeling’s First Flush teas are peachy and greenish, and there is a lot of romanticism surrounding them. Each year, Darjeeling fans around the world wait with baited breath for the First Flush to arrive - so these teas fetch a premium. The Second Flush teas, which exhibit a real muscatel flavor, are winey and spicey, and preserve well. (Bannerjee says the truest muscatel flavor comes only 2-3 weeks a year, when the aphids - green flies - chew on a small number of leaves as they grow, impeding their growth and bringing out this special flavor.) Monsoon teas are generally used in teabags and blends, as they are stronger. Autumnals are stronger than the second flush.

Crafting a Fine Tea

Darjeeling has a highly customized system of manufacture, during which it caters to the country’s and/or individual buyer’s tastes, be it for a stronger tea, like those in the U.K. desire, or a lighter tea, like the Japanese prefer.

The crafting of Darjeeling tea begins in the field. Workers begin plucking at 7am, when the tea is still covered with dew, until 4pm, usually picking the fine top “two leaves and a bud.” They bring their bounty to the factory to be weighed two or three times a day because the leaf has to start the processing close to when it is picked, as it will otherwise begin changing chemically in the basket.

|

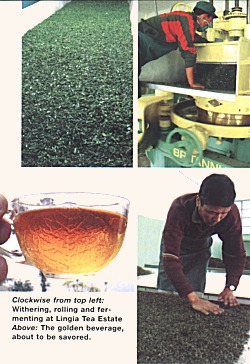

The Orthodox style of manufacture used in Darjeeling requires much time and care. After weighing, the leaves are spread out on troughs with the utmost of care, because if the leaves break, quality automatically begins to degrade, and this may damage the tea so much that it cannot be rolled. It is on these troughs that the process of withering, or removal of moisture, is carried out. Many say that the quality of a Darjeeling’s taste is “in the wither” and the tea garden managers pay particular attention to this stage of manufacture. Withering takes anywhere from 2 hours up to about 20 hours depending on humidity, climate, and time of year. Seventy-five percent of moisture is removed with cool air fans, which is replaced with hot air if the leaves are wet from rain or mist. In the Unorthodox manufacture, which is never done in Darjeeling, only 30% of moisture needs to be removed, and withering can be completed in 2 or 3 hours, as hot air is always used.

Next, the tea is rolled on a rolling machine, where the tea is subjected to a rolling movement under pressure which twists the leaf. The main purpose of this step is to prepare the leaf for fermenting by rupturing the cell membranes so that oxygen begins to act with its polyphenols, a main element of tea, also called catechins. Care is taken not to provide too much heat from the friction of the rollers because this can damage the essential oils, which are developed during this time. Some very delicate teas are rolled by hand.

Tea is then brought to the “fermentation room,” where the tea is oxidized - flavenols combine with oxygen in the air, developing the unique flavor of Darjeeling over a period of two to four hours. The rolling and oxidation rooms need to be exposed to cool, fresh air, so usually this part of the factory is open to the outdoors to let the mountain air in to mingle again with its tea leaves.

The leaf is then taken for “firing,” or, drying, to stop further fermentation by deactivating the enzymes, and to remove almost all of the remaining moisture in the leaf, hopefully down to about 2% moisture content. The tea dryer exposes the leaves to hot dry air at regulated, varying temperatures for 20 or 30 minutes. Tea is then graded by size through vibrating wire mesh sifters. Very delicate teas are hand sifted with flat baskets with various sized openings.

The sifted teas are often labeled as the following, with variation depending on the garden: whole leaf teas are FTGFOP - Fine Tippy Golden Flowery Orange Pekoe; the “brokens” (smaller, broken leaves) are TGBOP - Tippy Golden Broken Orange Pekoe; and “fannings” (dust-like particles) are OF - Orange Fannings. Brokens and Fannings are both used in teabags.

Regular observation and control of temperature, humidity, duration and rate of moisture loss are all vital, and human observation through all of the senses is the only way to coax the best flavor and texture out of the leaves. Experienced tea managers assess moisture content merely by sight and touch. Smell and look of the leaves in the fermentation room set the timing for drying and so on.

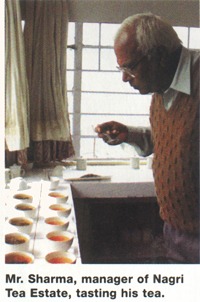

Of course, the final stage of crafting the tea is to taste it, and Darjeeling planters have a finely tuned sense of taste and a language to describe it that is all their own.

Before a tasting session begins, a table is set up in natural light where the dry tea, infused leaf and brewed tea are placed one in front of the other for each tea being tasted. The taster first checks the visual appearance and aroma of the dry tea. The infused leaves are set on top of the brewing cups to be inspected in the same way. The taster then sniffs, slurps and spits the brewed tea to identify the best. This stage of tasting is most important because Darjeeling is all about customization to the buyer’s tastes.