Exploring Specialty Teas in Southwest China By- Lydia Kung

Spring comes early to southwestern China, home to Yunnan Province, known for its ancient tea trees and Pu-erh aged tea, and to Sichuan Province, better known for its numbingly spicy cuisine than for its fine teas. One tea professor we met classifies teas into six categories: green tea, black, oolong, white, yellow, and brick teas. The last two are perhaps less familiar to tea drinkers, and one extravagant yellow tea is to be found in Sichuan, while brick teas, of course, are identified with Yunnan. Our group of six from the specialty tea industry arrived in Sichuan the third week of March, and yellow Mengding buds had already been finished two weeks earlier. The first flush in Sichuan and Yunnan begins a good half a month before Zhejiang’s season gets underway, affording tea growers in SW China a significant economic advantage. Here are some highlights from our trip:

Sunshine Tea from Ancient Trees

|

Parts of Southern Yunnan Province have beautifully sculpted hillside terraces of tea, occasionally interplanted with mango or other fruit trees. |

Heading out from JinHong in southern Yunnan, we traveled on roads lined with rubber trees, palms, and banana trees, leaving houses on stilts for higher ground, in search of ancient tea trees. Our journey took us to Ya-Nu Village, comprising some 100 households, with winding footpaths that lead upward to old tea trees. Our young guide clambered up quickly and effortlessly, testimony to her daily trips up the hills during tea season. Tender shiny new shoots were evident on trees averaging between five to seven feet in height. Returning to the village, we were shown into a small shed, where the fragrance of just plucked tea leaves permeated the room, and where soft, still pliant leaves had been strewn over platforms. Even though there was equipment for mechanically drying the leaves, we learned that the villagers prefer to sun dry the leaves. This partially processed tea is then transported to tea processing factories in towns two to three hours away. We were treated to this “Yunnan Sunshine Green,” reflecting a traditional method of de-enzyming first, rolling, followed by sun drying, identified closely with Yunnan’s indigenous tea culture. While it is common for villagers in tea growing areas to drink tea in this partially processed state, Sunshine tea is not generally sold for consumption. The tea was robust in flavor, and in one local variation, the tea leaves are roasted (in a simple tin can) over fire, and water is poured into the tin, making a smoky brew.

At a Tea Research Institute Like its counterparts in Anhui, Fujian, Guangdong, and other tea producing provinces, the Yunnan Tea Research Institute has large experimental gardens in addition to its campus of laboratories. While the tea institutes in Zhejiang and Sichuan study the small leaf variety, Yunnan’s researchers, as one would expect, concentrate on the large leaf variety. Their gardens contain over 830 varieties of tea bushes, including new strains. When we were served the obligatory mugs of tea, we noticed the unusual combination of large and small leaves swirling in our cups. It was soon revealed that our tea was a hybrid that combines the best of the large and small leaf varieties (full flavor from the large leaf strain, but less bitterness from the small leaf variety). All of the teas from the institute’s gardens are certified as organic by China.

Pressed Pu-erh: the Raw & the Cooked

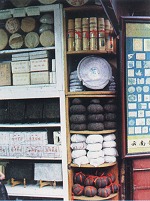

|

Many options exist for purchasing tea in Yunnan Province. This corner store offers various selections of Tuo Cha and Pu-Erh. |

No visitor to Yunnan can miss the sight or flavor of aged Pu-erh teas, and now even the Olympic rings appear as designs on Pu-erh cakes and bricks. We were interested in the growing popularity of “raw” or “green” pressed Pu-erh, evidenced by spiraling prices and wide appeal in Japan, Southeast Asia, France, and Eastern Europe.

The two or three major Pu-erh processing factories in Yunnan date from 1939-1942, but the Dali Tuo-cha Factory can claim a history from 1902. The town of Dali was long a collection center for tea, which in its pressed forms made for easy transport to neighboring areas and for easy subsequent storage. Pressed Pu-erh can take many shapes, ranging from mini-pumpkins, to huge disks, and calabashes five feet tall. The best selling Pu-erh are the more familiar bricks, cakes, and bowl-shapes (tuo cha).

If teas may be regarded on a broad continuum ranging from the non-oxidized to the fully oxidized, Pu-erh pressed teas go beyond these gradations. There are 10 generally accepted grades of loose Pu-erh, and factoring the number of years Pu-erh is aged, leaf Pu-erh itself becomes a complex category of tea, offering aficionados plenty to mull over. The addition of steam to loose leaf Pu-erh and its subsequent molding give pressed Pu-erh a distinctive and desirable character not found in loose leaf Pu-erh. (In fact, once steamed, pressed, and aged, these molded Pu-erhs may be steamed to loosen the tea once more for consumption and storage at home, a one-step process that obviates breaking off small pieces each time the tea is brewed.)

In making pressed tea, loose Pu-erh is first measured by weight; the tea is scooped into a small bag, placed into a mold, and the bag is knotted. (Teas may be blended for a specific price range, and a skilled worker can maneuver the scooping so that the better looking tea appears on the top surface of the cake or brick.) The bag is held in place by the worker, and the mold is heated briefly with steam. The mold is then inverted, the bag opened, and the formed tea is placed onto racks, where the tea dries for six to seven hours in a chamber with steam heat and circulating air. In large factories, we watched teams of three working through the first steps in a blur of motion with quick, deft hands. In Ya-Nu Village, a lone worker single-handedly went through each step steadily and methodically.

The above description may give the impression of one type of pressed Pu-erh when in fact there are two categories: the oxidized (“cooked” in Chinese parlance) and the “raw” or “green” (qing), made with tea leaves that have not undergone oxidation. In the latter category, there is a slow, natural transformation of green tea into a finished tea that has become oxidized from gradual aging. The highest priced cakes in this group show many silver-white strands, and look utterly different from the uniformly darker “cooked” cakes. Cakes and bricks have larger surface areas than tuo-cha and therefore oxidize faster, relatively speaking, than tuo-cha.

Just prepared qing beeng or “green” cakes are not great tasting; they require monitored storage with air circulation; spring brings some moisture and winter brings wind - all good for proper aging and justify the high prices for teas aged beyond seven or ten years. In one tasting of a green cake, stored for about five years, the brew was a bright amber, lighter than a traditional Pu-erh, but the flavor had a pleasant astringency and more fragrance than loose leaf Pu-erh or “cooked” Pu-erh cake. What had once been whitish tips on the cake had turned tan colored with time. On another occasion, we were brought a qing beeng made in 1986; with some ceremony, small pieces from the perimeter were broken off and brewed for us. Served in gong-fu cups, the taste was soft, the familiar Pu-erh aroma long and lasting, and the tea was good for several infusions.

Fresh tasting Pu-erh may be an oxymoron, but green cakes and bricks are evidently prized for the character that green tea can impart, albeit slight but still detectable even after years of aging. The flavor is less earthy than the cooked variety, but perhaps it is the dynamic, evolving character of green bricks that makes them so appealing to Pu-erh connoisseurs, as opposed to the more static quality of cooked Pu-erh. Green pressed Pu-erh, when tasted at different stages (say, three years - the minimum, five years, seven years), will show markedly distinct flavor nuances - to be savored slowly and then perhaps to be stored away again.

Taiwan Growers in Yunnan Paralleling the move to the mainland from Taiwan by entrepreneurs in other fields, we saw the development of gardens managed by tea specialists from Taiwan. Plucked from trees over several hundred years old, tippy leaves are harder to reach, but the very inaccessibility of these tea trees also means they have not been exposed to chemical fertilizers or pesticides. Growers in the Jing Mai mountain area of Yunnan claim that tea from these old trees container higher polyphenol levels than tea from bushes. Organic green, white, oolong, and Pu-erh teas are being produced from this historic tea area.

Yellow Tea in Sichuan

A long bumpy ride on roads that truly did call for SUV’s took us to Gao Xian, “High County,” where we came upon the tail end of the first spring plucking. As we walked to the processing plant, we passed a woman with a bright pink fabric bag; she had picked about half a kilo of tea buds from her day’s labor in the tea garden. She had been picking only buds, but even these were later sorted by hand before further processing. For Yellow tea, these tips are gently de-enzymed by steam for about 30 seconds, after which a clean cloth is placed over the warm leaves, allowing the generated steam to do its work on the leaves and also allowing the leaves to “breathe.” (For Green teas, such as Sichuan’s lovely Bamboo Leaf Green, the leaves are allowed to rest a bit after the steaming stage, to bring down the temperature of the leaves. Then the leaves are cooled before they are rolled.) For Yellow tea, it is this extra smothering process that forces the leaves to yield greater fragrance, simultaneously rendering a yellow gold brew and resulting in leaves with a yellowish cast. Sichuan Mengding is not a rolled tea, and is covered for about eight hours. Another famous Yellow tea, Jin Shan, is covered for only two hours, after which the leaves are rolled. As one might expect from the extra step, only buds or budsets are made into these costlier Yellow teas, with a distinctive character recognizable by those who savor this tea. At a later stop where we were treated to new Mengding, our Sichuan tea host remarked upon entering the room that the tea seems to have been overheated - this observation from only the fragrance of brewed tea yet to be poured; she was proven right when we tasted the tea!

The Tea Dept. at Sichuan Agricultural University

One of China’s leading learning centers for planting, animal husbandry, forestry, food sciences, and engineering, this university in the town of Ya’an with its 20,000 undergraduates and 14 PhD programs includes a tea department comprising seven faculty members. The area surrounding the university produces some 15,000 M/T of tea each year, with a target set at 50,000 M/T in another five years. About 30% of Sichuan’s teas are black teas, with green teas comprising sixty percent, and the balance made up by specialty teas. With its earlier season, Sichuan produces a significant amount of tea that is shipped to other parts of China for further processing. Current research efforts among the university’s faculty focus on earlier flush leaf size, pesticide resistance, crop yields, and cold tolerance, among other topics.

Disseminating updated information to improve the growing skills of tea growers and controlling the pesticides to which farmers have access are part of the Tea Dept.’s work. China’s first batch of organic teas was produced in Lin’an County in Zhejiang in June 1990. At present approximately 8,000 hectares in China have been certified by China’s Agricultural Certification Center, and the annual production of organic teas in China is about 8,000 M/T, or about 1.1% of the country’s total tea production. Sichuan started later than provinces such as Anhui and Jiangxi, and now boasts seven gardens near Le Shan producing 50 M/T of organic teas.

“Authentic” Teas & Origin Gardens

|

Wrapping Pu-Erh Beengs: Once pressed and dried, Pu-Erh "beengs" are carefully wrapped in their traditional paper. |

A visit to the Bamboo Leaf Green Tea Factory in Chengdu offered a glimpse into a state-of-the-art tea processing plant. The facility was operating at full capacity during this third week in March, processing tea that had been plucked from late February (given low rainfall this season), with three shifts working 24 hours on exquisite, high value tea buds. Next would come buds with one leaf, followed by buds with two leaves, all collected from outlying tea gardens. This particular factory was notable for its obvious and substantial investment in equipment and quality control, combined with very expert hand sorting and meticulous grading, better than we had seen elsewhere. Innovative package design also marked this as a very forward looking company, with wide ranging plans for domestic marketing and distribution. We took particular notice of the use of a hologram on their packaged teas as a sign of authenticity. As the manager of the company explained, his direct distribution to retailers in China is one way of combating counterfeiting of his brand in the domestic market. This is why he chose not to sell bulk teas within China, since he would not be able to control quality once the teas left his factory. His vigilance is admirable given the context of intellectual property violations elsewhere in the country, and it raised the broader question among our group of whether a tea such as Dragonwell still qualifies as a Dragonwell if it was not grown in Zhejiang.

The impetus behind the production of famous teas from parts of the country not originally identified with these teas, of course, comes from the high prices these well known teas can fetch overseas and in the domestic market. One professor at the Sichuan Agricultural University was adamant in his insistence that only Dragonwell from Zhejiang can be properly named and sold as Dragonwell, and he applied this principle to other sought-after teas. Growers we met, naturally, took more equivocal positions, and in fact, we were not always able to identify the “imposter” in blind tastings, although on occasion leaf appearance may give clues as to origin.

Given the strictures of teas’ micro-environments, it is not a simple matter to grow An-Xi TiKuanYin outside Fujian, Tung Ting Oolong outside Taiwan, or Keemuns outside Anhui. Nevertheless, with rising disposable income in urban centers, greater conspicuous consumption and lavish gifting, the demand for expensive, “name” teas in China is growing rapidly. This trend is evidenced by the burgeoning of tea tasting salons and tea culture showrooms, replete with all the accoutrements that tea demonstrations seem to require. Years ago high quality teas were not always to be found in China’s tea shops, since many top grades were destined for export. Happily this is no longer the case; in fact, as with other name-brand consumer goods, knock-offs or genuine, some teas are marketed at startling, astronomical prices. As to our tea hosts’ preferences, they reserve their enthusiasm for each season’s first crop of famous Greens and floral Ti KuanYin’s.

Lydia Kung is an importer and wholesaler of specialty teas at Eastrise Trading Corp.